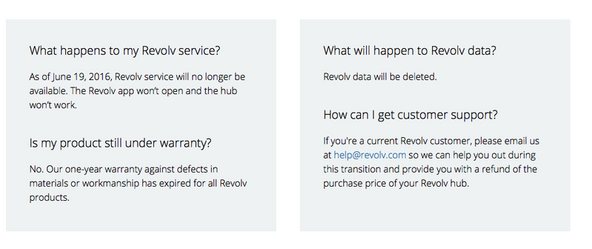

Nest Labs, pioneering overlords of our smarthome future, is about to do something pretty inhospitable to customers. On Sunday, they will pull the plug on Revolv—a home automation hub that Nest acquired almost two years ago. If you own a Revolv, your home will shut off. Your lights will turn off. Your doors will stay locked—or unlocked. Your sprinkler system will stop working. All that automation that you painstakingly set up? It’s quitting.

On June 19, Nest will brick people’s smart homes—and owners can’t do a thing to stop it.

The Revolv shutdown is more bad news in an epic run of bad news for Nest Labs. Nest CEO Tony Fadell recently stepped down after a tenure marred by stalled product releases, recalls, and in-house complaints about leadership. And the Revolv debacle didn’t engender Fadell any additional goodwill. Arlo Gilbert, a self-professed “home automation nut” and Revolv owner, publicly called Fadell out over the shutdown. Even employees of Google, which owns Nest, were openly critical of the decision to sunset Revolv.

The market is exploding with web-connected, software-enabled devices. Smart fridges that monitor your groceries, share pictures, and keep shopping lists. Collars that report on your pet’s activity levels. Home automation hubs—like Revolv—that let owners control their house from a single app. Hell, even cars are pretty much web-connected computers on wheels; they’ve got enough lines of codes in them to lasso an ox.

IOT devices are dependent on ongoing support—regular updates to keep the gadget secure and fully functional. Sure, that smart rectal thermometer might have felt a solid investment during your last late-night, fever-hazed Amazon shopping spree. But the thermometer only works as long as some poor software engineer is hired to keep its companion app working. And how long is that gonna be? A few years before your intelligent thermometer is as dumb as your decision to buy it in the first place?

Admittedly, obsolescence of this sort isn’t too big of deal for cheap, novelty items. But it is a big deal for larger purchases. Like appliances, which we expect to last for a decade or so. Samsung’s smart refrigerator, The Family Hub, would be a 300-pound, temperature-controlled brick without regular updates. (The company already has a spotty record supporting previous smart fridge generations.)

But the Revolv situation is worse because it’s more deliberate. Nest isn’t ending support—they are turning off the device off entirely. Gilbert, who is about to be the proud owner of a Revolv paperweight, explains what happens when a company can shut off your smart home: “My house will stop working. My landscape lighting will stop turning on and off, my security lights will stop reacting to motion, and my home made vacation burglar deterrent will stop working. This is a conscious intentional decision by Google/Nest.”

And why can Nest do that? Because you don’t really own any device with embedded electronics. Not wholly. You pay for the hardware, but the software (the part that actually makes your gadget work) belongs to the company that created it. And they can do what they please with it.

The Revolv story “raises a lot of questions: Questions about the ‘Internet of Things,’ about property rights in physical objects and about whether American intellectual property law goes too far,” writes Glenn Harlan Williams for USA Today. “And at the moment, I think the answers to those questions are that the ‘Internet of Things’ is stupid, property rights in physical objects don’t get nearly enough respect and American intellectual property law definitely goes too far.”

He’s right. IP law does go too far. And not just because intellectual property trumps your physical property rights. Also because you’re not allowed to take your property back—not without getting handcuffed by US copyright law.

Let’s say Nest tromps into your home and turns your Revolv into a hockey puck. But let’s say you’re a pretty savvy programmer. And you decide to crack open that hockey puck, use the (working) hardware infrastructure, and write your own operating system for the device? It would be a hell of a lot of work—but it’s possible.

Except you’re not allowed to.

Climbing into your device and taking control of the code isn’t something that manufacturers like. So some companies put digital locks over that programming. Pick the lock, and you could be in violation of US copyright law. The penalty? Jail time and a couple hundred thousand dollars worth of fines—just for reprogramming a device that you own. (Thanks, DMCA.)

“Ownership ought to mean something. When you buy a cellphone, or a car, or a home-automation controller, it should belong to you, not the company that ‘sold’ it to you. And if intellectual property law says otherwise, then Congress should change it,” Williams concludes.

Lawmakers and activists are trying to restore some of those property rights. Right now, the Copyright Office is conducting a study into problems that come with “embedded software in everyday products”—a challenge pretty much encapsulated by Nest’s execution-style killing of Revolv. In Congress, Texas Republican Blake Farenthold has been trying to pass YODA, the You Own Devices Act, since 2014. YODA would give purchasers legal ownership of the software in their devices—but the legislation has never made it past committee. And in New York, lawmakers are considering Fair Repair legislation that would give owners the right to fix dead or ailing devices—even if that fix requires tinkering with the code.

I hope Revolv getting shoved out the Nest will be the tipping point for reform. Still, that’s not much consolation for Revolv owners, who still get their smart homes bricked remotely. Because until something changes, companies can waltz into your house like a cyberpunk grim reaper and snuff the light right out of your smart stuff.

Header image courtesy of Nest Labs

One Comment

Thank you for recommending a nice article.Excellent and satisfactory post. It will beneficial for everybody.

Thanks for sharing one of these wonderful posts. It is extremely helpful for me.

Earth Pakistan Property Portal

Faisal Bashir - Reply