This is the third article in our ongoing series of posts on the history of screwdriver bits. We’ll be posting one a day leading up to the launch of our Manta Driver Kit and Mahi Driver Kit on Tuesday, April 24.

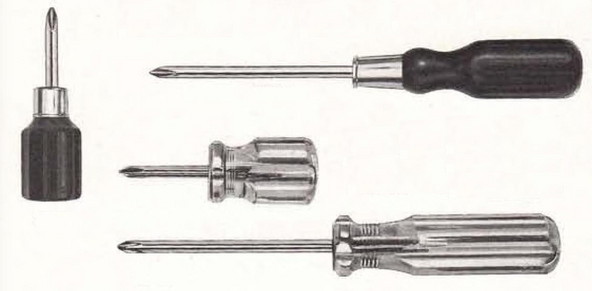

Trusty. Iconic. As all-American as Ma’s apple pie. Yes, the Phillips screwdriver.

Bearing the name of a Portlandian businessman who didn’t even invent it, the Phillips is the reigning standard in most American toolboxes. Henry F. Phillips bought the screw design from inventor John P. Thompson, who wasn’t able to muster up any commercial interest for his screwhead. Phillips was obviously a better (or luckier) salesman—or else we’d all have Thompson screwdrivers in our toolboxes right now.

But the Phillips wasn’t always “The Chosen One.” Back in the early 1900s, the Robertson was Henry Ford’s first choice for a high-torque screw for his Model T. But P. L. Robertson—inventor of the eponymous screw and driver—refused to license his design, having been screwed over by a previous licensing arrangement in England. Ford, needing the license to ensure a steady and reliable supply of screws, looked elsewhere. And found the Phillips.

But—aside from Phillips’ superior salesmanship—what made the Phillips so successful in the early days of industrial manufacturing? Well, the Phillips is built for more torque, but it’s also designed to “cam-out” under too much torque. On the surface, that might seem like a counter-intuitive thing for a screwdriver to do. But those curves on the cross-blades help the driver slip out of the socket rather than break when under too much pressure. This feature saves both tool and workpiece—especially important in places like an assembly line or on a factory floor.

The pointed bit design and gentle outward curve on each of the four blades also makes this bit “self center” when inserting the bit into the fastener. And once socketed, the bit and fastener have a fantastic amount of surface area in the direction of applied force. Increased applied force means a significantly tighter hold than the traditional slotted screw and driver, which is exactly what Ford and other manufacturers were looking for. From anchoring tiny watch pieces to securing car frames—and through every medium: wood, plastic, and metal—the Phillips screwed its way to the top.

As screw-turning technology improved and automatic torque limiters became standard in even the most basic power drills, the cam-out design has become both irrelevant and limiting. (Some manufacturers are now using anti-cam-out Phillips bits. Others have switched bits entirely.) Though it was designed by—and for—a bygone era of American manufacturing, that hasn’t spelled the end for this trusty fastener.

Despite its flaws, the Phillips head is emblazoned on our logo for a reason: it’s the ultimate symbol of hardware openness. The Phillips driver is ubiquitous—everyone has one. And when a manufacturer uses Phillips screws instead of security screws, they’re sending a message that their device can, and should, be opened. The same Phillips screwdriver you use to tighten your eyeglasses can be used to service a smartphone. And the Phillips #2, a household heavyweight, fits everything from light switches to cars. With the simple twist of a screw, you’re in control of your stuff.

So, when you pull out a tiny Phillips bit from your Manta Driver Kit or Mahi Driver Kit, wield it proudly: you’re part of the resistance. And, rest assured—that Phillips #2 screwdriver in your junk drawer will be useful for decades to come.

While you’re here, check out our previous posts on the Flathead and the Robertson. And be sure to join our mailing list—you’ll be the first to find out when the Manta Driver Kit and Mahi Driver Kit drop on Tuesday.

0 Comments